The long-lasting battle of women engineers

"I am an energy engineer, and the energy sector is one of the least gender diverse sectors among the different types of engineering." Beatrice Cordiano is our onboard scientist, expert in energy, environment and sustainability. For the International Women's Rights Day 2022 whose theme is #Breakthebiais, she tells us more about her own experience and why we need more women in technical jobs.

Beatrice Cordiano, on board scientist

It’s no secret that even today if you walk into an engineering firm the number of women you will see is very little. Until the last century, society used to believe that women could not comprehend machinery to any degree.

Proving the world wrong

It may seem a well-established formal academic discipline, yet engineering began to be taught in universities in the late 700s only. The foundation of the École Polytechnique in Paris in 1794, which was intended to teach military and civil engineering, served as a model to persuade other universities to include engineering as an academic subject. There, female students started being admitted only in 1972, almost two centuries later.

For decades women have been doing engineering works holding a training in mathematics or science yet being denied an official degree in engineering and just being offered a certificate of completion. This was unfortunately not only the case of engineering but of many other disciplines. Women were made to look after the house and take care of the family, they were looked upon as curiosities when they set foot in technical circles. They have long been regarded as unable to understand the complexity of engineering.

Ada Lovelace

Despite these struggles, many women fought their entire career to prove the world wrong. This is the story of Ada Lovelace, who was a mathematician and the very first computer programmer way before the invention of the computer, Emily Warren Roebling, who supervised the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, and Beulah Louise Henry, known as “Lady Edison” for her several inventions.

World War II called many men to arms, some to produce armaments, some to design aircraft, some others to plan battleships. It is with this shortage of men that women obtained the right - which men have had for a long time - to enrol in engineering programs. It was then that the number of women attending a technical education suddenly increased, contributing to the revolution that altered society’s perception of what women could or could not do.

The leaky pipeline

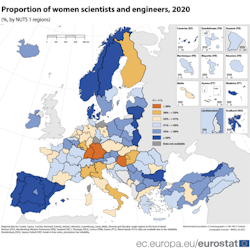

In 2020, 41% (or 6.6 million) of scientists and engineers across the EU were female. This is a big achievement considering that back in 2008 this percentage was 32%. Yet, this value is still low and mostly it does not represent the totality of countries: in Italy for instance, where I studied, women are still very little represented in engineering firms.

Proportion of women scientists and engineers, 2020

Nevertheless, I cannot say that women aren’t keen on science and that they do not enroll in such disciplines. Women do like science a lot and they do study it at university.

Where does the problem lie, then? Let’s take a pipeline. If we want a certain amount x of water at the outlet, we need to make sure to feed the pipeline with the same amount. That’s not all, we also need to ensure that the pipeline doesn’t leak. This pipeline spans from early education up to the adult career and it describes how women are progressively lost from STEM fields becoming an underrepresented minority. We lose potential women scientists and engineers at every stage of the pipe. It is a very leaky pipeline the one we have.

Beatrice Cordiano

Why do men make it to the other side of the pipeline better than women do? There are so many reasons why this gender gap in science occurs. Among these is the misconception in media and toys, which might instil in young girls’ minds the idea that engineering involves fixing things and getting your hands dirty and that is a men’s thing.

Then comes the stereotype about gender roles and the lack of a female model: engineering is traditionally a bunch of weird bespectacled men in shirts discussing in front of a technical drawing and our models are “just” great men like Tesla, Edison, Armstrong, Marconi. Not to mention further in the career life the gender bias in hiring, in the workplace, in work evaluation and promotions.

Engineering has always been male and as a woman it might sometimes be hard to imagine yourself in such a manly environment. Even when performing equally, women may feel less confident about their abilities.

Therefore, if we want more women in STEM, increasing the inlet flow doesn’t solve the problem but fixing the leaks does.

School visit in New Caledonia

Being a woman in engineering, being a woman in energy

I am an energy engineer and the energy sector is one of the least gender diverse sectors among the different types of engineering. Of the different energy specialisations, mine, namely renewable energies, is one of the best represented gender wise: 32% of the workforce are women (versus 22% in the overall energy sector), yet while 45% of them work in administration, only 28% hold technical jobs. The gap widens even more when it comes to senior management roles: here only 10.8% is female.

For me a career in energy engineering was never a question, I loved maths, physics and solving problems and I have always been fascinated by energy. I have always felt encouraged by everyone around me and never was I told that this choice was not made for girls, yet when I got into university the feeling of being a minority popped up sometimes. In team projects, I was often the only girl in a group of 5. In the whole class and out of more than 100 students, we were 30 girls.

Of all the professors I had in 5 years at university, I could count on the fingers of my both hands the female ones. However, this has not limited me and I have never felt unsuited to this kind of world. On the contrary, I learnt to think in a way I was not used to and I taught my male colleagues to rethink the unknowns of a problem with a new approach.

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

Engineering is about problem solving and if problems are solved by people of the same sex, mindset and socio-economic background, it is very likely that solutions will not take into account all the variables of the problem. For example, when designing an urban space women will definitely consider street safety, men might not. When designing an air conditioning system, men and women could not agree on the thermal comfort. Like these ones, there are a lot of other examples. Problem solving is biased and dependent on previous experiences.

Energy is a basic need for everyone, both male and female, its challenges are evolving and to be able to respond innovatively and inclusively we need to ensure a variety of approaches which only comes from a diversity of minds. We need more girls in engineering, we need more girls in science. After all, if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

To go further

More women join science and engineering ranks - Eurostat, 2022

Cross-Cutting activities relevant to all energy sectors and sources including modelling, and women's participation in clean energy - International Energy Agency (IEA), 2021

Active Participation of Women Essential to the Global Energy Transformation - International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 2018