Renewables in Africa and the Kenyan example

As Energy Observer starts sailing through African waters, our production team went on the ground to understand the energy challenges and leviers of this continent. During their trip to Kenya, Agathe Roullin and Beatrice Cordiano – our reporter and energy expert- had the chance to understand how renewables can support a clean and just transition in developing countries, through the example of geothermal energy, of which Kenya is one of the pioneers in Africa and in the world.

Wind turbines in Ngong Hills, Kenya

Eyes on Africa

Africa. One fifth of the world population, 6% of the global energy demand and 3% of the energy-related emissions to date. Figures that speak loud if you think that Europe, for instance, hosts half of the population with respect to Africa, consumes twice as much and has already emitted 10 times more. That’s what we call climate injustice. But why is that so?

Africa is home to 33 out of 47 least-developed countries in the world (source: UN) and one of the multiple reasons is that here lack to electricity access hits more than 40% of the population, namely about 600 million people. Electricity access is an indispensable factor for development. Education, healthcare, food conservation: none of them is possible without electricity.

Energy Observer's arrival in Brazil

Now, by 2050, 2/5 of the world’s children will be born here and the continent will be home to 2 billion people. If Africa’s development will be regardless of the environment, the global transition to a low-carbon economy will be extremely slowed down, so the continent needs to feed its own social and economic development and it has to do it clean. A lot of pressure, a big responsibility, and a huge challenge for developing countries. How can Africa increase the energy access and ensure energy security while shaping a new and sustainable roadmap to get there? The equation is complex, but the paths are there.

Room for renewables

Africa will have to work on two fronts: adding renewable generation capacity on one hand and increasing transmission and distribution infrastructures on the other hand.

Fortunately, resources do not lack: the continent possesses one of the best solar resources in the world with about 7900 GW of solar technical potential, followed by 1753 GW of hydropower potential, 461 GW of wind, as well as geothermal in some regions of East Africa.

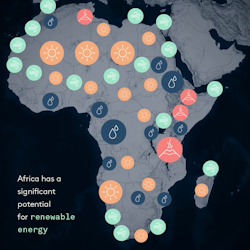

Africa's potential for renewables

Even if many of these resources are still often underutilised, some of the countries where Energy Observer plans to stop are already exploiting these clean sources and can proudly boast a green power generation mix. That’s the case of Kenya, where about 90% of the power comes from renewables.

Indeed, electricity is just a component of the energy a country needs -there’s energy for transports, industries, heating and cooking too- and in countries where access to electricity and electricity demand are still very limited, it covers just a little share of the whole energy mix. Nevertheless, in the coming years this slice of the cake is expected to get bigger and bigger.

Kenya, the geothermal El dorado

At the African scale, East Africa is the main area of exploitation of geothermal activity. Here, along the Rift Valley, a continuous tectonic fault stretching over 6000 km north to south and running through countries such as Ethiopia, Djibouti, Tanzania and Mozambique, is home to a high volcanic activity, whose estimated 20 GW geothermal potential is only partially exploited. One country leads the way, Kenya, while others are trying to catch up without any concrete achievements to date.

Hell’s Gate National Park, about 90 km northwest of Nairobi, is the centre of the Kenyan renewable revolution. Here, zebras, giraffes and buffalos cohabit with fumaroles, endless pipes and power plants. Around the world, wells need to be drilled down to about 3000 to 4000 m, in Kenya some of them are only 900 m deep, which combined to hot water temperatures of up to 300 °C, make geothermal energy particularly cost-effective.

Geothermal exploration in Kenya started around the mid-1970s, in a context of global oil crisis and changeable hydroelectric grid, when the government changed its strategy to avoid power rationing. Some years later, in 1981, the first geothermal power plant in Africa was inaugurated: Olkaria I. Everything started with a 15MW turbine, then expansion followed. Other turbines were installed, other well drilled and today Kenya ranks 6th worldwide for geothermal installed capacity with its 962 MW -enough to power more than 4 million homes a year - and hopes to have 1600 MW up and running by 2030.

Geothermal power plant in Olkaria

Wellheads: Kenya’s pride to develop geothermal faster

Geothermal powerplants operate at capacity factors around 90%, meaning that - unlike wind and solar - they can supply steady and continuous energy to meet base load demand. Nevertheless, geothermal energy accounts for less than 1% of global electricity generation capacity and that is mainly due to its high upfront costs and long project development periods.

Narrowing down the perfect spot, drilling wells, constructing pipes requires a lot of money: one well can cost up to 6 million USD. And time too: the powerplant has to be fed by steam from multiple wells, which are often left open for years after being drilled waiting for the completion of the central plant. This can sometimes discourage private investments and thus quick deployment.

Here’s where wellhead powerplants come into help, making geothermal projects more feasible and anticipating electricity and revenues generation. Fun fact : Kenya has been the first country in the world to make use of this technology.

Geothermal power plant in Olkaria

These smaller geothermal power plants can be constructed directly on top of the drilled wells, they’re modular and simple to build and they allow to harness the steam which would otherwise be wasted while waiting for the main plant to be ready. So, while a classic geothermal power plant runs thanks to the steam of tens of wells, wellheads produce power through the steam of a single well. That’s how Kenya, on its way to build its 7th geothermal power plant at Olkaria, manages to inject an extra 83.5 MW into the grid thanks to its 21 wellheads, that’s not peanuts.

This country has become an undisputed regional leader in terms of geothermal power and like it, other countries – Ethiopia and Djibouti in particular - are looking to develop this sector.

Renewables could support Africa on several aspects: not only they could help it close its energy access gap, which today remains an obstacle to socio-economic and human development, but they could also help reduce vulnerability to external shocks caused by the change in fossil fuels’ price and create jobs. This, together with the vast renewable potential of this huge continent, cannot but leave hope for a just and clean energy transition.