The interconnection of the ecosystems at the mercy of mankind

For this World Environment Day, we try to decipher the phenomenon of sargassum and the notion of the interconnection of ecosystems that hangs in a fine balance, the key to which is beyond our grasp and often weakened by human activity. Words by Katia Nicolet, a doctor in marine biology aboard Energy Observer.

Everything, in nature, is connected. Our actions have an impact on our environment that is tangible, albeit indirect, not just in our immediate vicinity but also on the other side of the world. The fertilisers spread in the fields of America and Europe, as well as the deforestation of the Amazon, are having an influence on the natural balance of the ocean and causing ecological catastrophe in the Caribbean.

Everything is connected

Humans have a tendency to describe, classify, quantify and define everything around them, putting each species, each habitat or ecosystem into a little box with well-defined edges. Perhaps it is somewhat reassuring to classify what we see around us in a bid to better understand and even control our environment. Here though, nature is poking fun at our human artifices. Everything, in nature, is interconnected.

In the calm waters of the Atlantic is a sea without borders, without shores and without easily definable limits, the Sargasso Sea. This Sea is created by four major marine currents, which form a gigantic vortex measuring 3,200km long and 1,100km wide. Inside this vortex, far from any continent, the waters are low in nutrients and as a result they are surprisingly blue and crystal-clear. The winds here are practically non-existent, and a lot of boats have drifted here, floating around aimlessly, awaiting a salutary breath of air. Their passage is slowed even more by a surface layer of dense seaweed: sargassum.

Sargassum, a unique ecosystem

Sargassum weed is one of the only types of seaweed that reproduces by fragmentation, directly in open water, without ever needing to attach itself to a substrate. It forms in waters rich in nitrates and phosphates in the Gulf of Mexico, where it finds all the nutrients necessary for its development. It then starts drifting and is carried along by the Gulf Stream as far as the calm Sea that bears its name.

Here, the sargassum clumps together into rafts, completely carpeting the surface and creating a unique ecosystem, which we sometimes refer to as the golden rainforest of the sea due to the yellow colouring of the sargassum. This floating canopy serves as a refuge for hundreds of species, which hide amongst the ‘leaves’, sometimes taking on the same hue to better camouflage itself. Such is the case for the Sargassum frogfish, a species which can only be found beneath these rafts of seaweed.

Fish hiding in seagrass

The young sea turtles also come and reside amongst the seaweed after leaving the beach where they hatched. With juveniles and small species of fish attracting the bigger ones, the Sargasso Sea is also home to tuna, marlin and sharks. In all, there are some 122 species of fish, 100 species of invertebrates and 4 species of sea turtle whose lives revolve around the sargassum, not to mention the sea birds, which feed here or rest on the surface.

Diving under gulfweed

Little-known interconnections

This distant ecosystem is also essential for the survival of the species we find close to home. Since Aristotle’s time right up to the present day, scientists have been focusing their energies on one question, without ever being able to come up with an answer: where and how do eels reproduce? We currently know that eel larvae reach the shores of Europe and America and then head upriver to grow and develop in the fresh water of the marshes. They spend 10 years of their life there in fact, still at an immature stage, before beginning their 5,000km migration bound for the open ocean and ultimately the Sargasso Sea. Here, in the dark, deep waters carpeted in a floating canopy, the mature eels die… Thus far, no scientist has witnessed their reproduction. However, one thing for sure is that this species classified as ‘critically endangered’, depends on sargassum for its reproduction.

A balance upset by human activity

Unfortunately, today this unique ecosystem is under threat. In the North Atlantic gyre, where the Sargasso Sea is located, there lies another sea: a sea of plastic waste amassing, piling up and creating what we refer to today as the 7th continent. This plastic pollution is causing hundreds of marine species to die from strangulation or intestinal obstruction. The plastic never biodegrades and slowly breaks down into smaller pieces, thus polluting the entire food chain, from young fish to sperm whale. This waste thrown away in the middle of nowhere, thousands of kilometres away, is endangering all the inhabitants of the Sargasso Sea.

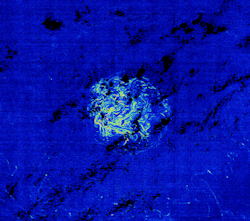

Since 2011, the sargassum itself has been causing major problems along the Caribbean coast and the shores of West Africa. For some still unknown reason, the sargassum is more prolific than normal, and rafts of seaweed measuring several hundred square metres have been washing up on the beaches.

Beach cleaning in Martinique

Guadeloupe alone has collected over 300,000 tonnes in the space of a year. Once it makes landfall, this seaweed decomposes, giving off putrid odours and harmful gases like hydrogen sulphide. It also clutters up the beaches, preventing the mature turtles from laying their eggs there or their little ones from leaving the nest. It is essentially a complete role reversal then as the seaweed was originally beneficial to these creatures.

Gulfweed bank in the Caribbean Sea

An accumulation of sargassum decomposing in the lagoons also promotes the overproduction of hundreds of bacteria, which make the water anoxic, meaning it has low levels of oxygen. This lack of oxygen and light cause many sessile species like coral and seagrass to die. This seaweed filters out and also forms a concentration of a significant number of pollutants as it approaches land, including chlordecone, arsenic as well as 28 heavy metals including aluminium, copper and manganese. This two-pronged pollution of the beaches is a genuine ecological, economic and social catastrophe for the people living on the Atlantic coast.

Several hypotheses attempt to explain the proliferation of sargassum outside their natural distribution zone. Is the modification in marine currents due to climate change? Or is the increase in nitrates and phosphates in the major rivers of America, Africa and Europe due to the intensification of agriculture and deforestation? The truth surely lies in multiple factors and today scientists are trying to solve this equation.

One thing for sure: everything is connected.